Thomas Rowlandson, Description of a Boxing Match, 1812

BRITONS then who boast themselves Inheritors of the Greek and Roman Virtues, should follow their example, and by encouraging Conflicts of this magnanimous Kind, endeavour to eradicate that foreign Effeminacy which has so fatally insinuated itself among us, and almost destroy the glorious spirit of British Championism, which wont to be at once the Terror and Disgrace of our Enemies.

– Handbill for Broughton’s Amphitheater, 1747.

It was with rhetoric such as this that the retired boxing champion Jack Broughton sought to persuade the young gentlemen of London to come forward and receive tuition in the “manly art of boxing” at the training academy which he had founded on Oxford Road in 1743. Boxing was already undergoing a process of cultural transformation by the time Broughton published his advertisement and ultimately this was to see the sport elevated from the realms of the street brawl and the circus tent to sit alongside hunting, riding and fencing, in the pantheon of sports enjoyed by the wealthiest members of Georgian society. Boxing’s appearance in satirical prints during the long eighteenth-century therefore reflects both the growing awareness and popularity of the sport among the middling and upper-class customers of London’s print shops and also tells us something about contemporary notions of politeness, class and gender.

The origins of boxing as a spectator sport lay in the prize-fights that formed a staple part of the entertainment typically offered by the summer fairs and backstreet gambling dens of late seventeenth century England. These fights would usually take place alongside other violent spectacles, such as cock-fighting and bear-baiting and were often split into several different rounds in wrestling and bare-knuckle boxing would be mixed with armed combat featuring sticks, knives and even broadswords. The levels of violence in these early fights was exceptional by modern standards but rarely proved to be fatal, with matches typically coming to an abrupt halt once blood was drawn. The German traveller Zacharias von Uffenbach recalled that a fight between two men at the Bear Garden in Hockley in 1710 was stopped when one of the participants received a blow to the face “with such force that one could hear the sword grating against his teeth” and “not only the whole of his shirt but the platform too was covered in blood.”

The use of weaponry was to remain a common, even dominant, feature of the prize-fight until well into the eighteenth-century and in some cases fighters were given more recognition for their skills with the blade than they were for their abilities as a boxer. For example, the advertisements which Hogarth produced for the prize-fighter James Figg (1695 – 1735) neglected to mention Figg’s abilities as a boxer and yet he was famous for having won all but one of the 270 matches he fought. It’s an omission which reflects the attitude of Figg’s wealthy patrons towards a sport which was still largely seen as being the sole preserve of the lower classes. One contemporary pamphleteer summed these views up by asserting that gentlemen should avoid mixing with the “meanest rabble” at boxing matches and argued that the strength and hardiness of the boxer was little more than a reflection of his lowly station in life. Attitudes such as this were beginning to change though and by the middle of the 1740s armed prize-fighting had largely fallen into abeyance, thanks to the rise of a new cultural phenomenon based around the philosophy of the polite. Politeness dictated that differences should be settled between gentlemen in a fair and civilised fashion and its advocates became vocal critics of excessively violent practices such as dueling and armed prize-fighting. These criticisms hinged on both a humanitarian criticism of the use of potentially lethal force and a moral argument which said that it was unfair to expect amateurs to risk their lives in armed fights against trained professionals. It was, remarked one critic of duelling, “base, for one of the sword, to call out another who was never bred to it, but wears it only for fashions sake”.

The use of weaponry was to remain a common, even dominant, feature of the prize-fight until well into the eighteenth-century and in some cases fighters were given more recognition for their skills with the blade than they were for their abilities as a boxer. For example, the advertisements which Hogarth produced for the prize-fighter James Figg (1695 – 1735) neglected to mention Figg’s abilities as a boxer and yet he was famous for having won all but one of the 270 matches he fought. It’s an omission which reflects the attitude of Figg’s wealthy patrons towards a sport which was still largely seen as being the sole preserve of the lower classes. One contemporary pamphleteer summed these views up by asserting that gentlemen should avoid mixing with the “meanest rabble” at boxing matches and argued that the strength and hardiness of the boxer was little more than a reflection of his lowly station in life. Attitudes such as this were beginning to change though and by the middle of the 1740s armed prize-fighting had largely fallen into abeyance, thanks to the rise of a new cultural phenomenon based around the philosophy of the polite. Politeness dictated that differences should be settled between gentlemen in a fair and civilised fashion and its advocates became vocal critics of excessively violent practices such as dueling and armed prize-fighting. These criticisms hinged on both a humanitarian criticism of the use of potentially lethal force and a moral argument which said that it was unfair to expect amateurs to risk their lives in armed fights against trained professionals. It was, remarked one critic of duelling, “base, for one of the sword, to call out another who was never bred to it, but wears it only for fashions sake”.

Boxing was to survive and flourish precisely because it could be accommodated within the sphere of the polite entertainment. This was achieved during the course of the 1730s and 40s by the gradual introduction of rules and proscribed techniques that were designed to ensure fair play and limit excessive brutality. As enthusiasm for this more refined form of pugilism began to grow among the middling and upper classes, boxing venues slowly migrated from the rural margins of London to the fashionable heart of the city. Other concessions to the tastes of a wealthier class of boxing fan included the introduction of boxing gloves, or ‘mufflers’, designed by Broughton to protect his genteel pupils from “the inconveniencey of black eyes, broken jaws and bloody noses.” By the early 1750s even those who continued to criticise boxing were willing to grudgingly acknowledge that it was “infinitely more characteristic of Old English prowess, and less destructive of human life” than duelling or the prize-fights of the previous generation.

By the 1780s the patronage of the Prince of Wales, as well as the utilisation of print to bolster the popularity of champion boxers such as Daniel Mendoza and Richard Humphries, raised boxing to new heights of popularity. This prompted an influx of aristocratic fans and patronage into the sport, with various Dukes and Lords conferring handsome stipends on their preferred champion as a means of securing the substantial amounts of money that were now being wagered in West End boxing clubs. Participation levels also rose among the upper classes, with the Daily Universal Register despairingly questioning whether “black eyes and bloody noses will shortly… replace patches and dimples in all beautiful countenances” and other newspapers rushing to publicise accounts of fights featuring aristocratic pugilists such as the Earl of Barrymore. The elevation of boxing to the status of an elite sport during the final years of the eighteenth century even prompted some entrepreneurs to try hosting staged fights which conformed entirely with aristocratic principles of politeness. In 1791 when Daniel Mendoza opened his own boxing school in the Strand he informed his would-be patrons that “the manly art of boxing would be displayed, divested of all ferocity, rendered equally as neat and elegant as fencing [and] conducted with the utmost propriety and decorum.” One businessman even took this a step further by opening an exhibition near Leicester Fields where visitors could pay to watch stage-managed fights which were paused in order to allow a commentator to explain the techniques being used to the audience. This process of gentrification was ultimately responsible for the gradual decline of the original tradition of bare-knuckle boxing, which was to begin a slow retreat back to the underground during the nineteenth century.

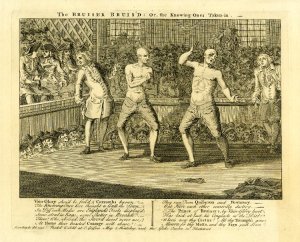

While the encroachment of the middling and upper classes into the world of pugilism may have curbed some of the excesses of the earlier prize-fights, boxing was to retain a resolutely proletarian image throughout the period and the blurring of otherwise rigid class lines which occurred at boxing matches was to become a  reoccurring theme within contemporary satire. This social fluidity was not always presented in a positive light and a number of the earliest prints to feature boxing present an ambivalent or even hostile view of the upper class male who goes ‘slumming’ among the crowds at a fight. Peter Griffin’s The Bruiser Bruis’d: Or, the Knowing-Ones Taken-in (1750) for example, sneers at the wealthy young “coxcombs” opt for the unseemly spectacle of the boxing match over the glory of the field of battle at “Quiberon and Fontenoy”. While Louis Philippe Boitard listed boxing alongside swearing, gambling and “ogling” in the list of vices that are eroding the morals of the British gentleman in The Present Age (1767).

reoccurring theme within contemporary satire. This social fluidity was not always presented in a positive light and a number of the earliest prints to feature boxing present an ambivalent or even hostile view of the upper class male who goes ‘slumming’ among the crowds at a fight. Peter Griffin’s The Bruiser Bruis’d: Or, the Knowing-Ones Taken-in (1750) for example, sneers at the wealthy young “coxcombs” opt for the unseemly spectacle of the boxing match over the glory of the field of battle at “Quiberon and Fontenoy”. While Louis Philippe Boitard listed boxing alongside swearing, gambling and “ogling” in the list of vices that are eroding the morals of the British gentleman in The Present Age (1767).

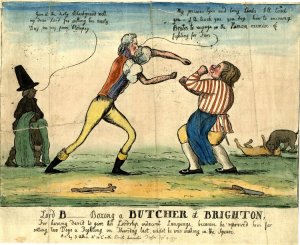

By the 1780s boxing’s integration into the world of aristocratic male entertainment had become so complete at to make further arguments about the possible dangers associated with the distortion of class boundaries effectively redundant. Caricatures of the late Georgian period therefore tended to unreservedly celebrate the  egalitarian nature of boxing as a reflection of the liberties enjoyed by British subjects. Thus we see The Prince of Wales and a butcher linking arms to carry the victorious Richard Humphries off the field in Johann Ramberg’s The Triumph (1788) and a dispute between a peer and a humble tradesman being settled by a fight in William Dent’s Lord B___ boxing a butcher at Brighton (1791). This favourable view of boxing probably reached its apogee during the Regency era, when George and Robert Cruikshank produced a wealth of prints which revel in the mixing of high and low culture at boxing matches. Robert Cruikshank’s beautiful Going to a Fight (1819) for example, the liveried carriages of the rich can be seen running alongside open wagons carrying a parties of dustmen to see a fight. Similarly, the illustrations that Robert and his brother George produced for Pierce Egan’s Life in London (1820-21) show a trio of fashionable young swells receiving lessons in pugilism and carousing with retired prize-fighters.

egalitarian nature of boxing as a reflection of the liberties enjoyed by British subjects. Thus we see The Prince of Wales and a butcher linking arms to carry the victorious Richard Humphries off the field in Johann Ramberg’s The Triumph (1788) and a dispute between a peer and a humble tradesman being settled by a fight in William Dent’s Lord B___ boxing a butcher at Brighton (1791). This favourable view of boxing probably reached its apogee during the Regency era, when George and Robert Cruikshank produced a wealth of prints which revel in the mixing of high and low culture at boxing matches. Robert Cruikshank’s beautiful Going to a Fight (1819) for example, the liveried carriages of the rich can be seen running alongside open wagons carrying a parties of dustmen to see a fight. Similarly, the illustrations that Robert and his brother George produced for Pierce Egan’s Life in London (1820-21) show a trio of fashionable young swells receiving lessons in pugilism and carousing with retired prize-fighters.

Boxing prints also reveal something about contemporary notions of gender and the different cultural spheres that men and women were thought to occupy in eighteenth-century society. The popularisation of the sport  coincided with a sudden shift in attitudes towards the playful transgression of gender roles which had characterised elite social activities during the middle decades of the century. In the wake of the disastrous loss of the North American colonies, the effeminate male ‘macaroni’ and the lady who indulged in the masculine, military-inspired, fashions of the late 1770s, were pilloried by caricaturists as symbols of national decline. Isaac Cruikshank’s St George & the Dragon & Madlle riposting (1787) reflects the mood of the times in showing the Price of Wales being reduced to tears after a scuffle with the transvestite Chevalier d’Eon. The practice of pugilism was therefore increasingly seen as a cultural antidote to the corrosive influence of dandyism and a robust physical assertion of the masculinity and marital prowess that Britons believed had made their forebears great. As Pierce Egan was to write in the introduction to his

coincided with a sudden shift in attitudes towards the playful transgression of gender roles which had characterised elite social activities during the middle decades of the century. In the wake of the disastrous loss of the North American colonies, the effeminate male ‘macaroni’ and the lady who indulged in the masculine, military-inspired, fashions of the late 1770s, were pilloried by caricaturists as symbols of national decline. Isaac Cruikshank’s St George & the Dragon & Madlle riposting (1787) reflects the mood of the times in showing the Price of Wales being reduced to tears after a scuffle with the transvestite Chevalier d’Eon. The practice of pugilism was therefore increasingly seen as a cultural antidote to the corrosive influence of dandyism and a robust physical assertion of the masculinity and marital prowess that Britons believed had made their forebears great. As Pierce Egan was to write in the introduction to his history of the sport, it was necessary for the country as a whole to encourage its men to engage in activities that “tend to invigorate the human frame, and inculcate those principles of generosity and true courage, by which the inhabitants of the English Nation are so eminently distinguished above every other country… by a native spirit, producing that love of country, which has been found principally to originate from… vulgar Sports! John Smith’s caricature Boxing made easy or Humphreys giving a lesson to a lover of the polite arts (1788), also offers a perfect summation of the juxtaposition between the heroically John Bullish figure of the pugilist and the pathetic form of the Frenchified fop.

history of the sport, it was necessary for the country as a whole to encourage its men to engage in activities that “tend to invigorate the human frame, and inculcate those principles of generosity and true courage, by which the inhabitants of the English Nation are so eminently distinguished above every other country… by a native spirit, producing that love of country, which has been found principally to originate from… vulgar Sports! John Smith’s caricature Boxing made easy or Humphreys giving a lesson to a lover of the polite arts (1788), also offers a perfect summation of the juxtaposition between the heroically John Bullish figure of the pugilist and the pathetic form of the Frenchified fop.

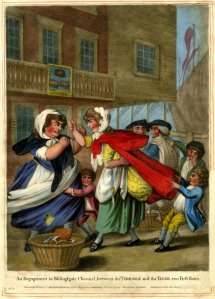

Fights between women were also generally looked on as a gross distortion of accepted gender norms and although some contemporaries were willing to grudgingly acknowledge the existence of such practices, they often went to great lengths to point out that they remained confined to the disreputable margins of society. The author of an account of the fight between two women that was held in the yard at the rear of the Crown Inn in Cranbourne Alley in 1803 for example, sought to extinguish any pangs of sympathy his readers may have felt by loftily informing them  that “the two females (we cannot call them women)” were residents of the slums of St Giles and well-known to the local magistrates. This is a view which is echoed in caricatures such as An Engagement in Billingsgate Channel, between the Terrible and the Tiger, two First Rates (1781) and Rowlandson’s depiction of a fight between two “drabs” in the Miseries of London (1807-08) series, which both stress the both the physical ugliness and lowly status of the fighting female.

that “the two females (we cannot call them women)” were residents of the slums of St Giles and well-known to the local magistrates. This is a view which is echoed in caricatures such as An Engagement in Billingsgate Channel, between the Terrible and the Tiger, two First Rates (1781) and Rowlandson’s depiction of a fight between two “drabs” in the Miseries of London (1807-08) series, which both stress the both the physical ugliness and lowly status of the fighting female.

Finally, the most common reference to boxing in caricature prints was as a metaphor for the conflicts that characterised domestic politics and international affairs throughout this period. One of the earliest references to pugilism in graphic satires was A Political Battle Royal Design’d for Broughton’s New Amphitheatre (1743), which shows the various parliamentary factions preparing to slug it out in order to settle the matter of Walpole’s succession. This humorously reductive view of British politics was to remain a constant theme in English caricature throughout the eighteenth century and beyond and was to feature in political prints produced by Richard Newton, William Dent, Isaac Cruikshank and William Heath, amongst others.

The pugilistic motif also appears frequently in prints dealing with foreign affairs and particularly those produced between 1793 and 1815, when the British love of boxing was often seized upon by patriotic writers as being symbolic of the  embattled nation’s struggle against a France and her allies. The writer William Oxberry’s introduction to the 1812 essay Pugilistica modestly suggested Britain’s love of boxing “demands the Admiration, and Patronage of every free State, being calculated to inspire manly Courage, and Spirit of Independence – enabling us to resist Slavery at Home and Enemies from Abroad”. A view which is reflected in prints such Olympic games or John Bull introducing his new ambassador to the grand consul (1803) Boxiana- or- the fancy (1815). Indeed, by the time William Heath sat down to engrave Non intervention or the peaceable appearance of Europe (1831) the figure of the pugilist had become conflated with that of John Bull himself.

embattled nation’s struggle against a France and her allies. The writer William Oxberry’s introduction to the 1812 essay Pugilistica modestly suggested Britain’s love of boxing “demands the Admiration, and Patronage of every free State, being calculated to inspire manly Courage, and Spirit of Independence – enabling us to resist Slavery at Home and Enemies from Abroad”. A view which is reflected in prints such Olympic games or John Bull introducing his new ambassador to the grand consul (1803) Boxiana- or- the fancy (1815). Indeed, by the time William Heath sat down to engrave Non intervention or the peaceable appearance of Europe (1831) the figure of the pugilist had become conflated with that of John Bull himself.

Great post, as always. I did want to share a little more about the Hogarth trade you used. While Hogarth and Figg were friends, Hogarth did not design his trade card. It was actually done by Anna Maria Ireland who passed it off as an original Hogarth.

You can see the British Museum’s page on the card at

http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/search_the_collection_database/search_object_details.aspx?objectid=3296682&partid=1&searchText=james+figg&fromADBC=ad&toADBC=ad&numpages=10&orig=%2fresearch%2fsearch_the_collection_database.aspx¤tPage=2

Well spotted! Thanks.

First Shakespeare and now Hogarth… Is there anything that the Ireland’s didn’t try to forge?!

In that case I suppose that the image of Figg carrying a quarterstaff which appears in Plate two of The Rake’s Progress could also be used as evidence of the primacy of armed combat in prize-fights of the early eighteenth-century.

Yes, imagery was a fundamental element of the best pugilistic writing in this period, as explored in ‘Writing the Prizefight: Pierce Egan’s Boxiana World’ (2013)

Pingback: The Greatest African American and Afro-American Martial Artists in History | Out of This Century

Pingback: Pugilism: A Gentleman’s Sport | Jane Austen Variations