Curious Sporting Advertisement

A Picture of the Fancy going to a Fight at Moulsey Hurst, (measuring nearly 14 feet in length) containing numerous Original Characters, many of them Portraits; in which all the Frolic, Fun, Lark, Gig, Life, Gammon and Trying-it-on, are depicted, incident to the pursuit of a Prize Mill: dedicated, by permission, to Mr Jackson, and the Noblemen and Gentlemen composing the Pugilistic Club… Throughout the Picture, not a Pink has been overlooked, nor an Out-and-Outer forgotten: the whole forming ‘A bit of good Truth!’

Sporting Anecdotes, Philadelphia, 1822.

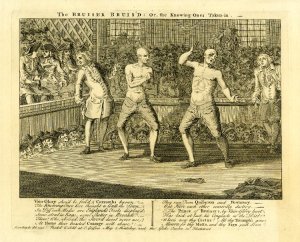

This was how the sporting journalist and raconteur Pierce Egan chose to describe Robert Cruikshank’s Going to a Fight to the American readers of his journal Sporting Anecdotes in 1822. The print had first appeared in England three years earlier and was the latest in a long line of collaborative projects between Egan and the elder Cruikshank. Egan had known Robert and his younger brother George since 1812, when he had employed both young men to provide illustrations of famous pugilists to decorate the early editions of Boxiana. A friendship seems to have been formed, spurred on no doubt by a shared love of carousing, gambling and sports. It’s may be possible that the Cruikshanks even saw something in Egan which reminded them of their late father Isaac, a man who had felt equally at home in low taverns and gambling dens. The journalist was also something of a minor celebrity in sporting circles, so much so that it was said that his “presence was understood to confer respectability on any meeting convened for the furtherance of bullbaiting, cockfighting, cudgeling, wrestling, boxing and all that comes within the category of ‘manly sports'”. Egan would therefore have been able to introduce his young friends to the leading boxers of the day and ensure that they could rub shoulders with aristocratic followers of the ring and the turf as easily as they could with the denizens of a St Giles drinking pit.

Going to a Fight was evidently conceived as a joint project between Egan and Cruikshank Senior. Robert provided the artistic skills necessary to convey the anticipation and excitement of a big prize fight, while Egan used his knowledge of the sport to write out a detailed key explaining the narrative behind such a lengthy composition. It also seems safe to assume that Egan was also behind the plan to include portraits of well-known followers of the sport in the design, ensuring a ready audience for the finished print among London’s well-to-do sports fans. The decision to portray a real fight, which had taken place on 3rd April 1817, and the endorsement of John Jackson’s Pugilistic Club also helped convey a sense of realism and authority upon the project. Going to a Fight was published by the company of Sherwood & Jones on September 1st 1819 and issued in two formats – either packaged in a custom-made mahogany box from which the print could be gradually unreeled, price 14s plain and £1 coloured, or it could be cut into lengths and mounted in a frames at a cost of £1 12s plain and £1 18s coloured.

But without further ado, let’s join Mr Cruikshank and Mr Egan as they prepare to take us off to Moulsey Hurst to enjoy a bout between the acclaimed London-Irish boxer Jack Randall and his opponent Richard West, otherwise known as West Country Dick.

We arrive in Regency London on a warm spring evening in 1817 and are immediately ushered into the Long Room at the rear of the Castle Tavern in Holborn. The Castle was home to London’s boxing fraternity and boasted a prize ring of its own. Tonight the barroom is crowded with the raucous members of the Daffy Club, a society formed under the leadership of Mr James Soares and dedicated to the enjoyment of the twin pleasures of drinking and sports. The members gather around the table and over tumblers of ‘daffy’ (gin), begin to discuss and place bets on the outcome of tomorrow’s fight. Behind them on the walls are arrayed portraits of other famous pugilists, including Mendoza, Humphreys, Jem Belcher and even Jem Belcher’s dog, Trusty, who was himself a champion of the dog-fighting rings and thus considered worthy of a place among such august company.

the Castle Tavern in Holborn. The Castle was home to London’s boxing fraternity and boasted a prize ring of its own. Tonight the barroom is crowded with the raucous members of the Daffy Club, a society formed under the leadership of Mr James Soares and dedicated to the enjoyment of the twin pleasures of drinking and sports. The members gather around the table and over tumblers of ‘daffy’ (gin), begin to discuss and place bets on the outcome of tomorrow’s fight. Behind them on the walls are arrayed portraits of other famous pugilists, including Mendoza, Humphreys, Jem Belcher and even Jem Belcher’s dog, Trusty, who was himself a champion of the dog-fighting rings and thus considered worthy of a place among such august company.

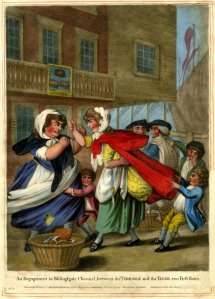

With a few mugs of gin in our bellies and our bets safely recorded in the Club’s  book, we move on to morning of the big fight itself. The common at Moulsey Hurst is well-known venue for prize-fights and cricket matches but it lies about 15 miles to the south-west of London and an early start will unfortunately be necessary to secure a decent pitch by the ring-side. The roads out of town are thronged with traffic and we see smartly liveried coaches competing with modest gigs and the wagons of tradesmen, to be the first through the turnpike at Hyde Park Corner and off onto the open road. Numerous pedestrians walk along by the roadside, some are also setting out early with the intention of watching the fight, while others are intent on taking the opportunity to make a profit, by fair means or foul, from the crowds. As we near the turnpike, we notice a pair of effeminate dandies mingling with the crowds. Unfortunately, they appear to be so deeply engrossed in a conversation about the merits of buff-coloured breaches or some such nonsense, that they’ve failed spot a young urchin who has snuck up on them and stolen their pocket books. Further down the road we come across another member of the maligned dandy species, being given a short, sharp, lesson in manliness by a gang of roughs. It appears as though this foppish fellow will have to colour-coordinate his cravat with a black-eye when he gets dressed tomorrow.

book, we move on to morning of the big fight itself. The common at Moulsey Hurst is well-known venue for prize-fights and cricket matches but it lies about 15 miles to the south-west of London and an early start will unfortunately be necessary to secure a decent pitch by the ring-side. The roads out of town are thronged with traffic and we see smartly liveried coaches competing with modest gigs and the wagons of tradesmen, to be the first through the turnpike at Hyde Park Corner and off onto the open road. Numerous pedestrians walk along by the roadside, some are also setting out early with the intention of watching the fight, while others are intent on taking the opportunity to make a profit, by fair means or foul, from the crowds. As we near the turnpike, we notice a pair of effeminate dandies mingling with the crowds. Unfortunately, they appear to be so deeply engrossed in a conversation about the merits of buff-coloured breaches or some such nonsense, that they’ve failed spot a young urchin who has snuck up on them and stolen their pocket books. Further down the road we come across another member of the maligned dandy species, being given a short, sharp, lesson in manliness by a gang of roughs. It appears as though this foppish fellow will have to colour-coordinate his cravat with a black-eye when he gets dressed tomorrow.

We drive onwards, past Hyde Park Barracks and out into the open country surrounding London. Past dust carts laden with rubbish, farmers driving their cows to market and even a group of fellow travelers who have fallen into an argument and are brawling at the roadside. The roads are packed and the air is thick with dust. As we fly by market gardens, commons and farmland, we pass overladen carriages which have collapsed under the weight of so many passengers, accidents involving the notoriously dangerous phaeton carriage and all manner of other traffic. Indeed, it seems at times as though all of London has upped-sticks and left town for the day. As we arrive in the town of Hampton we pause briefly and join the large crowd of boxing enthusiasts who have stopped to wet their whistles at the Red Lion Inn in the market square. Feeling suitably refreshed, we resume are journey with renewed vigour.

We drive onwards, past Hyde Park Barracks and out into the open country surrounding London. Past dust carts laden with rubbish, farmers driving their cows to market and even a group of fellow travelers who have fallen into an argument and are brawling at the roadside. The roads are packed and the air is thick with dust. As we fly by market gardens, commons and farmland, we pass overladen carriages which have collapsed under the weight of so many passengers, accidents involving the notoriously dangerous phaeton carriage and all manner of other traffic. Indeed, it seems at times as though all of London has upped-sticks and left town for the day. As we arrive in the town of Hampton we pause briefly and join the large crowd of boxing enthusiasts who have stopped to wet their whistles at the Red Lion Inn in the market square. Feeling suitably refreshed, we resume are journey with renewed vigour.

The spirits of our fellow travelers are evidently up by the time we reach Bushy Park and we join a number of carriages and gigs in a hell for leather dash across the open parkland for the banks of the River Thames. On arriving there we wait patiently to scramble aboard one of the many small boats and barges that will finally carry us all across the river onto the hallowed sporting turf of Moulsey Hurst.

We make our way across the field, past the circle of wagons which has been drawn up to act as a viewing platform for those standing near the back and through the huge crowd that is gathered around the makeshift boxing ring. From here we have a perfect view of the proceedings and can clearly see the noted members of the Pugilistic Club, dressed in their distinctive uniform of blue coat, yellow waistcoat and specially commissioned ‘PC’ buttons, taking up their places at the ringside. The members of the Club are able to confer this honour upon themselves as both the organisers of the fight and the providers of the twenty-five guinea prize pot which will be awarded to the victor. The umpires arrive next and take up their positions at opposite corners of the ring. And finally, here come the fighters.

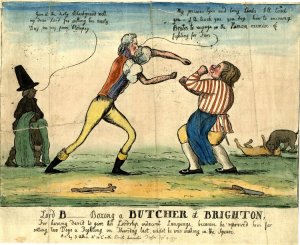

Tents selling beer, spirits and other refreshments have been pitched on the common since the morning and consequently the crowd is already thoroughly well lubricated by the time the fight starts at 2pm. A raucous wave of cheers, hoots and catcalls greets the boxers as they emerge onto the field, accompanied by their seconds and a bottle-carrier who will provide water, or whatever other restorative liquids are required during the course of the bout. The cheers are justified, Randall and West Country Dick are highly rated fighters and both are hitherto undefeated. Randall is the more experienced of the two but Dick has quickly acquired a reputation for both his stoicism and a deadly right-hand. It looks as though we’re in for a good fight.

The fight begins in earnest immediately and from the outset it is clear that Randall is the superior of the two boxers. He goes in close, steering clear of Dick’s dreaded right-hook and keeps his opponent on the ropes, sending him down in the second round with a fierce blow to the head. Randall and West Country Dick go at it in a spirited but inconclusive fashion for a further four rounds, until Randall suddenly catches hold of Dick’s throat and delivers a rapid succession of blows to his face, sending him tumbling to the ground in a shower of blood and prompting roars and cheers of “Bravo Paddy!” from the crowd. The West Country lad is stunned for a moment but proves his reputation for bravery is well-founded by rising to his feet and proceeding to battle on for a further seventeen rounds. It’s a valiant effort but the outcome now seems to be something of a foregone conclusion; Dick lands a few keen blows to Randall’s face and body, knocking him down on a number of occasions but is otherwise being comprehensively out-fought. The fight is finally called to a halt in the twenty-third round, when Randall lands a thundering upper cut in Dick’s stomach, which leaves him rolling on the floor winded and gasping for breath. The umpires declare the Irishman the winner and when West Country Dick is finally helped back to his feet, the two men shake hands and leave the ring.

Jubilation and scorn in equal measure from among the crowd! The wooden scaffold carrying the betting stall is immediately overrun by the ebullient followers of Jack Randall, while West Country Dick’s fans console themselves with another mug of ale as they contemplate the long walk home to London. The day isn’t over just yet though, and Moulsey Hurst now takes on something of the atmosphere of a country fair. For those sporting fans whose appetite for blood has still yet to sated, there is a bull-baiting contest taking place in one part of the field. A prize bull is tethered to a chain in the ground and then set on by a specially bred bulldogs. The winner, being the owner of the dog which can hang onto the angry bull’s snout for a sufficiently long amount of time, will be awarded with a dog collar cast from solid silver. We linger by this scene for a few moments but turn to leave just as the poor old bull is fortunate enough to exact its vengeance on a dog and its owner who have strayed too close. With the sun slowly setting behind us, we join the tired but thoroughly happy crowds on the road back to town.

Our old friends the Daffys have declared tomorrow to be the “settling day” for the fight and that members will convene at the usual time and place to settle their bets over a drink or two. The business of settling day is always transacted at Tattersall’s horse auctioneers, which is located just off Hyde Park Corner. We arrive there on a fine afternoon to find that a sale of prime bloodstock is already underway and various Daffys are to be found lounging around the elaborate neo-classical water pump in the centre of the courtyard. Money changes hands, drinks are drunk and yesterday’s fight is picked over in detail by these aficionados of the ring. And it is unfortunately here, in the convivial surroundings of Tattersall’s, that we must finally part company with the Daffys, Robert Cruikshank and Pierce Egan, leaving them to enjoy what’s left of a pleasant spring day in Regency London.