I’m back! The opportunity to sneak a post onto the blog finally appeared in the dying embers of 2022 and so here we are. Whether this becomes a regular occurrence in the year ahead remains to be seen, but for now let’s pour ourselves a festive drop and take a look at C.J. Grant’s first foray into the world of caricature magazines.

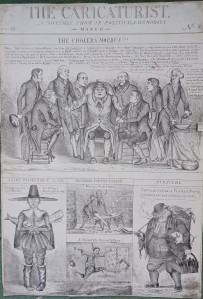

The Caricaturist, A Monthly Show Up was a produced by Grant, published by Edward King and sold from the latter’s “news agency office” [1] on London’s Chancery Lane from circa July 1831 until December 1832. Examples are scarce and frequently found in a mutilated state, with the masthead having been trimmed off (as with many of the examples shown here) or even the entire sheet cut up into scraps. As is so often the case with satirical prints from this period, those copies that have survived and found their way into institutional collections are not catalogued in any detail. [2] Nevertheless The Caricaturist is worthy of note for the obvious role it played in influencing the form and content of both of Grant’s most well-known works – The Political Drama (1833 – 1836) and Every Body’s Album & Caricature Magazine (1834 – 1835) – and also as an example of the way in which satirical prints were changing in the second quarter of the nineteenth-century, as new technologies and an influx of middle class consumers displaced the conventions of late eighteenth-century caricature.

At this point it’s perhaps worth our while to take a short diversion and explain the use of the word ‘magazine’ when talking about the satirical print trade of this era. While we think of a magazine as a glossy periodical consisting of text and pictures, our forefathers applied the word differently and indeed its use seems to have changed somewhat during the first three decades of the nineteenth century. The title ‘caricature magazine’ was initially used as a term of reference for an otherwise unrelated sets of single sheet prints that were bound behind a title page and sold either collectively or on a serialised basis. Its use in this context lent heavily on the military etymology of ‘magazine’ as the word for a place in which arms and ammunition were stored. It does seem coincidental that caricatures themselves had been referred to as ‘squibs’ – a slang term for a bomb – for a decade or two before ‘magazine’ seems to have crept into general use as a collective noun for sets of such prints.[3] But from 1825 onwards the word was associated with a specific type of satirical publication; folio-sized sheets carrying several smaller engravings which were published serially under a shared title. The format combined aspects of the humorous scrap album sheets that were becoming extremely popular during the 1820s, with the equally novel appearance of a graphic newspaper. [4] It took off rapidly after 1830 and several different titles were published in London, including most notably McLean’s Monthly Sheet of Caricatures or The Looking Glass (1830 – 1836), The Odd Volume (1834) and the aforementioned Every Body’s Album… It was claimed that the latter title eventually achieved sales figures numbering in the tens of thousands, if true, demonstrates that the most successful caricature magazines were comparable to national newspapers in the size and geographic spread of their audiences. [5]

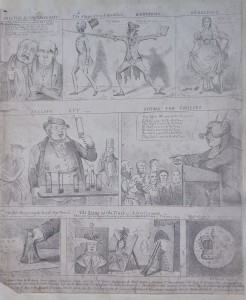

From the perspective of a customer walking into a print-shop in the early 1830s, the appeal of the format is self-evident; magazines offered the opportunity to purchase several smaller caricatures for the price of a single old-fashioned copperplate engraving. An advertisement for the first edition of The Caricaturist, which appeared in July 1831, indicates that Grant and King were not only aware of this but made in integral to their marketing. An advertisement for the first number informs us that customers can expect “nearly 30 original Lithographic Designs” arranged on four pages for a price of 1s. 6d. per uncoloured copy, making The Caricaturist “[t]he Cheapest Work of the kind” available. [6] This aggressive approach to pricing ultimately proved to be unsustainable and within twelve months the number of engravings had been cut by half. [7] But by then the magazine had an established viewership and it appears that – whether by accident or design – the earlier editions were effectively ‘loss leaders’ that allowed Grant and King to carve a niche for themselves in an otherwise crowded marketplace.

The Caricaturist offered its viewers a mix of social and political satire in each monthly issue. The social satires frequently reflect the contemporary taste for visual puns and are usually either wince-makingly unfunny or crassly insensitive by today’s standards. Issue No. 8 for example, published when Britain was gripped by the early phases of a global cholera pandemic that would kill several thousand people in London alone within a few months, features a small caricature of death making a pile of coffins as he gloats: “Who says Trade’s Dead”. Another panel from an unnumbered plate contains an engraving of a peg-legged naval veteran attempting to run by “Putting his Best Leg Foremost”. Other topics include the comic mixing of high and low culture, the dubious delights that supposedly await those emigrating to Britain’s antipodean colonies and the popular theatre. Grant had previously attempted to establish himself as a writer of comic theatre and evidence of his continued interest in melodrama and the stage appears in many his caricatures throughout the 1830s. [8]

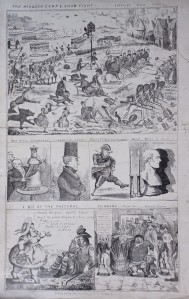

Political subjects dominated though and seem to have accounted for around three quarters of the images engraved for each issue. Unsurprisingly, given Grant’s blossoming association with the Radical movement which called for universal manhood suffrage and sweeping constitutional reform, the editorial tone of the satires is virulently and frequently violently anti-conservative in its outlook. The monarch, the Tory party and the various institutions of church and state that make up the establishment are represented as being engaged in a war against the interests and liberties of the British people. The theme of confrontation is applied literally to a number of frenetic battle scenes, including most notably TO BE or NOT to BE. That’s the QUESTION – A National to be Free She Only Wills It, [Plate 2] in which slapstick violence provides a light-hearted veneer to an otherwise deeply subversive image in which factory workers are shown massacring an army led by the Duke of Wellington. It’s a picture which reflects the radical tone that crept into the later editions of the series. For example, The Slumbering Lion from issue No. 10, shows us a heavily armed John Bull dozing ominously on the front bench of the House of Commons as he awaits the outcome of the second reading of the Reform Bill. Selling Off [Plate 3] sounds a similar warning note in its depiction of John Bull as a street vendor doing a brisk trade in miniature models of revolutionary guillotines. In this respect, The Caricaturist undoubtedly presaged C.J. Grant’s move towards a more uncompromising and aggressive form of satire that would find its fullest expression in The Political Drama.

While it’s impossible to quantify the level of commercial success the magazine enjoyed, it certainly seems to have gained recognition and found an audience. Newspaper commentaries praised The Caricaturist for being “designed with a great deal of whim and broad humour” [9] and called it “droll and full of spirit”, predicting that… “[t]he artist, Grant, is likely to acquire a high distinction”. [10] An anonymous contributor to The Athenaeum even admitted that: “We have laughed heartily over it, and have ourselves dispatched a copy to friends abroad, as likely to give them a good idea of the feelings at home – and we recommend others do the same.” [11] While it’s almost certainly the case that at least some of these commentaries were not genuine, the relative longevity of the title and the rapidly expanding list of provincial retailers willing to act as official distributors of The Caricaturist indicates that a degree of praise – even self-reverential praise – may have been justified. [12]

This naturally brings us to the question of why The Caricaturist seems to have been discontinued shortly after its 17th issue was published in December 1832. The simplest and most plausible explanation is that it had ceased to be profitable for its publisher. A review which appeared in The Satirist newspaper published around the same time as the magazine’s final issue suggests a potential decline in its fortunes:

THE CARICATURIST, or Monthly Show-up, boasts its accustomed share of whim. We wonder the artist does not make an effort to curtail the extravagance of his invention; his humour would be more relishable, and the general effect of his wit much heightened. The lithographing of this monthly satire is sadly executed. It would be to the interest of the publisher to place it in the hands of abler artists than those at present engaged upon it. [13]

However, I find this review intriguing and can’t help but wonder if it hints at a more complex story involving a breakdown in relations between Grant and King. The Satirist had made several favourable references to The Caricaturist in 1831 and 1832 before performing a sudden volte to attack Grant. Many of these reviews were little more than thinly veiled advertisements and the repeated use of similar phrases indicates the possibility of them being the work of a single hand – maybe even that of King himself. [14] The incongruous tone of this article, which praises The Caricaturist while simultaneously calling on it’s publisher to sack the artist responsible for producing it, gives the impression of a dispute between the two men being played out surreptitiously in the pages of The Satirist. Grant certainly seems to have had a disputatious temper and would go onto to engage in a very public argument with the printseller Gabriel Shire Tregear in 1835. [15] An advertisement for The Caricaturist which appeared in The Satirist in October 1831 indicates that King may not have been lacking in his capacity to make enemies either, as it ends with the slightly jarring declaration that:

The encouragement E. King has met with for his first numbers of the Caricaturist will stimulate him to greater exertions; assuring the Public, neither threats nor bribes shall deter him from pursuing that course which had given such general satisfaction. [16]

Whatever reasons lay behind the decision to bring The Caricaturist to a halt, it certainly appeared to mark the end of Grant and King’s commercial relationship. The latter seems to have abandoned the publication of satirical prints altogether after 1832 and chosen to focus on the sale of newspapers. [17] Grant’s career as a caricaturist was still in the ascendant and within 3-4 months he would go onto produce the first plate from The Political Drama series. The publication of another caricature magazine – Everybody’s Album… – followed a year later, arguably marking the commercial and creative peak of his career before he too tumbled back into obscurity.

Louis-Leopold Boilly Radicalism Thomas Dolby

References

- Weekly True Sun, 13th April 1834, p.24.

- British Museum No. 1995,1105.2 for a copy of issue no. 2 and Library of Trinity College Dublin OLS CARI-ROB 1296 for one of issue no. 12.

- For an early example see the frontispiece to Tegg’s Caricature Magazine (1807)

- The first such publication was The Glasgow Looking Glass (1825 – 1826)

- Thomas Dawson, who published the later issues of Every Body’s Album… claimed to have sold 39,000 copies per edition. This compares with an estimated circulation of 10,000 copies for each daily edition of The Times newspaper in 1834.

- The Age, 31st July 1831, p.7.

- The Athenaeum, 10th December 1831, pp. 806 – 807 indicates that the price initially remained unaltered but the size of the publication was reduced to “a single folio sheet [with] some twenty or more caricatures”. This did not remain fixed however and although the July 1832 edition was priced at 2s, it’s size had been increased to include a second page of engravings Library of Trinity College Dublin OLS CARI-ROB 1296.

- For more on Grant’s early career in the theatre and the influence of the popular theatre on his caricatures see M. Crowther, C.J. Grant’s Political Drama: Radicalism and Graphic Satire in the Age of Reform (2020)

- Ballot, 5th February 1832, p.3.

- Satirist, 4th September 1831, p6.

- Athenaeum, ibid.

- Ibid, 8th January 1832, p. 1. “Recently published by E. King. Chancery Lane, price 1s. 6d., No. V of a singularly novel and moral, graphical and quizzical, caustic and physical, political censorial and pictorial MONTHLY NEWSPAPER, entitled THE CARICATUIST, or MONTHLY SHEW UP… To be hand in Manchester, of C.H. Lewis, bookseller and general newspaper agent, 6 Market-street (by whom trade in this and the surrounding towns may be supplier) and of most printers, bookseller, and newsmen in the Kingdom.” A Mr Nightingale of the “Chronicle Office, Liverpool” became The Caricaturist’s second provincial wholesaler in the summer of 1832 – Ibid Satirist, 5th August 1832, p. 1.

- Satirist, 9th December 1832, p. 3.

- Ibid, 23rd October 1831, p.1., 8th January 1832, p. 1. & 5th August 1832, p. 1. The words ‘whim’ and ‘folly’ are repeatedly used in reviews and advertisements for the magazine and the phrase ‘hitting follies as they fly’ appears more than once, see and Athenaeum, ibid. Even if King did not write these reviews himself, his connection with the newspaper trade may have given him influence over their content.

- https://theprintshopwindow.wordpress.com/2014/06/29/guest-post-they-quarreled-somehow-g-s-tregear-c-j-grant/

- Satirist, 4th September 1831, p. 1, 30th October 1831, p. 1, 8th January 1832, p.1. & 6th May 1832, p. 1. The frequency with which this statement appears in King’s advertisements is perhaps indicative of a deliberately marketing ploy intended to amplify the impact of Grant’s satire on those who appeared in The Caricaturist.

- Weekly True Sun, 13th April 1834, p.24.

Thank you for your most recent interesting Blog on Grant’s Caricaturist, which was most illuminating.

I have a sheet from Everybody’s Album entitled “The Century of Invention, Anno Domino 2000, Or the March of Aerostation, Steam, Rail Roads, Moveable Houses and Perpetual Motion” .

This has an interesting subject-matter.

Assorted buildings on wheels are seen travelling along the Grand Northern Railroad on an elevated bridge pulled by a steam engine towards Birmingham—buildings bear the following advertisements: the Travelling Bazaar, an Establishment for Cast Iron Glass warranted not to crack, the Steamo Equestrian Travelling Company, J Bladder Balloon Maker, Villa of Taste and Zion Chapel.

Two gentlemen converse on a balcony of a building at Hampstead Heath Street discussing the exhaustion of the coal mines in the North of England and the news that a new coal mine is to be opened under Blackheath to supply the market.

There is an inn on top of a tall tower in the sky called “Sky High Inn and half Way House for Balloons”. Various steam driven road vehicles belching smoke from funnels can be seen travelling along roads, one advertising that 100 persons can be carried inside, with 120 outside and another that the trip between London and Edinburgh will be made in three hours (ie at a speed in excess of 130mph).

There is a race in the sky between winged travellers, the “Out of Sight Club and United Moonies”, flying to the moon.

I hope you find this of interest.

Your further Blogs are keenly awaited.

Jonny Duval

Thank you kindly.

It may interest you to know that the image you’re referring to was also printed on textiles. You can see an example here (although a stiff drink is advised before looking at the price): https://www.abebooks.co.uk/servlet/BookDetailsPL?bi=1076892442&searchurl=kn%3Dcharles%2Bjameson%2Bgrant%26sortby%3D17&cm_sp=snippet-_-srp1-_-title16#&gid=1&pid=1

Best wishes

Thank you.

Similar to William Heath ,The March of Intellect and March of Intellect 2 series of prints, which is my area of interest.