The residents of 54 Berners Street were awoken early one November morning in 1810 by the sound of chimney-sweep knocking loudly and incessantly on the door at the rear of the property. He had, the sweep explained to the bleary-eyed chambermaid who was eventually dispatched to investigate the cause of the commotion, been asked to call at the house to attend to an urgent job. After tartly informing the sweep that he had not been called for and that his services were definitely not required at such an ungodly hour, the maid promptly slammed the door in the puzzled man’s face and returned to her bed.

She had just settled back under the covers when the knocking began again in earnest. Flying downstairs in a rage and flinging open the door to give the insolent sweep a piece of her mind, the housemaid was surprised to find a completely different man staring back at her. He was also a sweep and like his colleague before him, claimed that he had been asked to call at the house before dawn to clean the chimenys. He was followed in quick succession by a third sweep and the a fourth, all bearing the same set of instructions. When the exasperated servant had finally finished turning the sweeps away, the sound of their retreating footsteps was drowned out by the rumbling of cartwheels, as wagons loaded with sacks of coal and baskets of fresh fish rolled into the back of the yard to deliver goods which their drivers claimed had been ordered by the household.

As dawn finally broke over Berners Street the trickle of tradesmen presenting them at the door of No. 54 turned into a besieging flood-tide, as this contemporary rhyme about the incident recalls:

The surgeons first, armed with catheters, arrive,

And impatiently ask is the patient alive.

The man servant stares – now ten midwives appear.

‘Pray sir does the lady in labour live here?’.

‘Here’s a shell’ cries a man, ‘for the lady wot’s dead’.

‘My master’s behind with the coffin of lead’.

Next a wagon, with furniture loaded approaches,

Then a hearse, all be-plumed and six mourning coaches,

Six baskets of groceries – sugars, tea, figs,

Ten drays full of beer – ten boxes of wigs.

Fifty hampers of wine, twenty dozen French rolls,

Fifteen huge wagon loads of Newcastle coals –

But the best joke of all, was to see a fine coach

Of his worship the mayor, all bedizen’d, approach;

As it passed up the street the mob shouted aloud,

His Lordship was pleased and most affably bowed,

Supposing, poor man, he was cheered by the crowd.

The mayor was followed by a succession of grand coaches carrying the directors of the East India Company and the governor of the Bank of England respectively, each of whom stated that they had been called hither to receive information on supposed frauds within their organisations. Even royalty did not escape a summons, with the Duke of Gloucester appearing to speak with an elderly retainer who was on his deathbed and wished to communicate news of some terrible scandal in the royal household.

By mid-afternoon the street was teeming with people; the anger of those who found they had been called to the address for no reason subsiding as they joined the growing crowd to laugh at the next cohort of unsuspecting dupes. The Lord Mayor of London however was far less sanguine in his response. He did not appreciate being dragged all the way across town to be made an ass of and to be hooted at by a mob of tradesmen. After storming out of No. 54 Berners Street, he directed his coach to the nearest magistrates office and demanded that the police take action. A party of constables was duly dispatched to disperse the crowd, a task which was made infinitely more difficult by the constant stream of newcomers who were still attempting to make their way onto the street in order to make a delivery or offer their services to the residents of No. 54. Eventually, a cordon of police constables was thrown across either end of the street and the siege of Berners Street was finally lifted, but it was to be long after nightfall before the fraught residents of the household could finally retire to their beds in peace.

The incident was soon dubbed the Berners Street Hoax by an inquisitive press, who lost no time in reporting on the matter in great detail. The tone of many of these articles was often surprising ambivalent, mixing disdain for the pranksters decision to play their joke on the respectable old widow who resided at No. 54, with a sort of grudging admiration of the sheer audacity of their actions. It was also not long before the press began openly speculating on the identity of those who may have been behind the trick.

One of the names that frequently appeared in connection with accounts of the hoax was that of precocious twenty-two year old playwright by the name of Theodore Hook. Hook had first come to public prominence in 1804 when, at the age of sixteen, he had composed and directed his own comic opera in the West End and he had enjoyed a moderately successful career in the theatre ever since. He was also a well-known society playboy who occupied a large part of his time with boozing, roistering and playing elaborate practical jokes on his friends and acquaintances. It was widely reported, both at the time and in articles which appeared decades later, that Hook had staged the prank in order to win a bet and prove that he could make a randomly selected house into the most famous address in London. Hook and a number of accomplices then spent several weeks penning hundreds, some say thousands, of letters inviting all and sundry to call at Berners Street. On the allotted day they also rented a room in a house opposite in order to watch events unfolding from a safe distance.

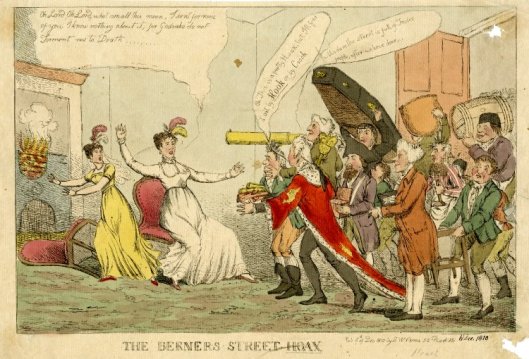

On 6th December 1810 S.W. Fores published a caricature on the subject by a budding fifteen year old artist called William Heath. The Berners Street Hoax shows an imaginary scene in which the besieging army of tradesmen comes bursting through the door of the victim’s parlour. The men carry an assortment of items ranging from wigs and firearms to barrels of beer and boxes of pills, with one of them informing the startled homeowner that “…the street is full of Trades people after we are done”. The lady of the house, who Heath depicts as being younger and probably a lot more attractive than the old widower who had been the victim of the prank, reels back in horror, exclaiming “Oh Lord, Oh Lord, what can all this mean, I sent for none of you, I know nothing about it, for Godsake do not torment me to death.” The Lord Mayor, who is shown at the front of the advancing mob wearing his official robes and carrying his mace, turns in an attitude which suggests imminent departure and says “Oh this is a pretty hoax, but I’ll find it out by Hook or by Crook.” A pointed reference to Theodore Hook’s rumoured involvement in the prank. Interestingly this appears to have been the only known caricature to have been produced which deals directly with the subject of the Berners Street Hoax. This seems somewhat odd given the fact that the amount of press coverage the incident received in the weeks, months and years that followed the event. Why was it deemed an unsuitable subject for graphic satire?

One possible explanation may lie in the pages of a biography of Hook published shortly after his death in 1844. The author suggests that the whole incident had been one orchestrated act of political satire, and that the real victims were the various dignitaries who had been lured to Berners Street to be exposed to the ridicule of the mob. It seems unlikely that this was ever Hook’s intent, as he would later go on to become an outspoken proponent of ultra-conservative political views, but it may certainly have been the case that many of his contemporaries chose to interpret the hoax in this way. The laws which governed the prosecution of seditious activity in Regency Britain certainly reinforced the notion that there was an inherent danger in any activity which undermined the respect and deference that the poor owed to those set above them in the social hierarchy. In 1804 Lord Ellenborough had handed down a ruling for seditious libel against a journalist who had pointed out the fact that the Prince of Wales was fat and unloved. The fact that the man proved quite convincingly that both of these statements was true was irrelevant – the prince was heir to the throne and therefore any attempt to denigrate him was a form of treason. The prevalence of attitudes such as these amongst many of the wealthy individuals that visited London’s printshops may have made the Berners Street hoax an uncomfortable subject for graphic satire, and this could be why it was largely ignored by the caricaturists of the day.

Pingback: Gobbets of the week #17 | HistoryLondon

Pingback: History Carnival 148 | William Savage: Pen and Pension

Pingback: The Berners Street Hoax | The Printshop Window | First Night History