Concerns about the potential dangers associated with the public display of caricature prints were raised almost as soon as printsellers’ windows became features of note among eighteenth-century urban landscape. The critics ranged from those who simply saw displays of satirical prints as a crowd-drawing nuisance, to those who considered them to pose a fundamental threat to the moral and spiritual wellbeing of the nation. Those who fell into the latter group often described caricatures as if they possessed a hypnotic quality and were capable of seizing hold of the minds of those who happened to pass by the printsellers window and corrupting them.

This argument was clearly articulated by one critic, calling himself ‘Perambulator’, whose thoughts on the subject were published in the Morning Post and Daily Advertiser of 5th September 1780. The author claims to have observed the crowds passing before the window of “the large [print] shop in St Paul’s Churchyard” and to have witnessed first-hand the disturbing power these “alluring objects of the most lascivious depravity” had to ensnare the “thoughtless and innocent”. A young man who was passing before the shop was literally transfixed by the sight of the “wanton looks [and] indecent dress”contained within the prints that decorated the shop’s windows and was unable to break free from the window’s gaze “til his sight is disgusted by indecency and shocked by obscenity”.

The number of printselling outlets was also multiplying across Britain and window displays of caricatures were becoming an increasingly common feature of urban commercial space. In the 1778 pamphlet Mild Punishments, Sound Policy, Dr William Smith complained vociferously about the quantities of lewd and offensive prints which were being exposed to public view in London. The practice had now become so flagrant, and the content of the prints so repugnant, he argued, that upstanding members of the community must feel compelled to take action to prevent a moral calamity:

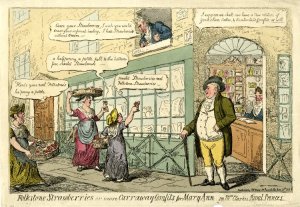

A 1774 mezzoting showing the front of Carrington Bowles shop at 69 St Paul’s Churchyard. This is almost certainly the shop at which ‘Perambulator’ claimed to have witnessed the power of caricatures to distract and inflame the mind of an innocent youth. Surprisingly the print itself confirms the view that printshops were often haunted by a rather salubrious cross-section of Londoners, including in this instance, a young rake, a lady of questionable virtue and a man who is being arrested by a constable.

These prints instill the most dangerous poison into the minds of youth, and seduce them into the ways of vice, by exposing to their view, in the most open and conspicuous manner, scenes only fit for a brothel. Such a scandalous nuisance should be checked; and if the magistrates do not put a stop to it, every lover of decency has the means in his own hands, by breaking the windows where such sights are presented.

While it’s easy for the modern reader to dismiss the complaints of these critics, which seem humorously quaint and naive in comparison to the standards of our own age, there was a grain of truth at the centre of many of their arguments. Graphic satire was changing markedly during the 1770s and 1780s, becoming far less formal and more florid in style, while also abandoning many of the traditional morality themes that had typified the prints of Hogarth’s age. And although there were still artists and publishers willing to produce prints with overtly moral themes in this period, such as Robert Dighton’s Keep Within the Compass (c.1785), the relative popularity of these designs was declining in comparison with more frivolous forms of social and political satire. These newer forms of caricature, which often dealt in the ephemeral subjects of fashion, city life and sociability, also physically displaced more respected and aesthetically accomplished prints from the windows of many of London’s printsellers. ‘Perambulator’ for example, lamented that the windows of the printshop in St Paul’s Churchyard which had once been decorated with portraits of “great or good men, either of past or present days… [are] now filled with prints that shock the modest and decent eye”.

Printshop windows also often did act as the backdrop for illicit and illegal activities. An outraged moralist searching for evidence of a link between caricature prints and indecent behaviour needed to look no further the records of London magistrates, which indicated that the crowds who gathered at printsellers windows often contained pickpockets and other petty thieves. Prostitutes were also known to ply their trade among the ranks of those who had gathered to idle away their time at the printseller’s window, as the playwright Oliver Goldsmith observed when he complained that such gatherings often consisted of little more than “quacks, pimps and buffoons… noted stallions [and]… more noted whores.” There is also evidence of more serious incidents taking place outside printshops, ones which really would give the prudish moral guardian of Hanoverian England cause for concern, and it is to one of these scandals that we must now turn our attention.

The front of S.W. Fores shop at the Sackville Street corner of Piccadilly in a caricature by Isaac and George Cruikshank from 1810

It was a summer afternoon in the middle of August 1825, and a sixteen year old surgeon’s apprentice named Thomas Hodson was admiring the large collection of caricature prints that were displayed in the windows of S.W. Fores’ printshop on the corner of Sackville Street and Piccadilly. He had been there for a short while when he became aware of the presence of a well-dressed elderly gentleman standing beside him. The two quickly fell into conversation about the prints and the older man offered to show the teenager some items from his own collection, which he just happened to have in a small folio that he carried about his person. Digging deep into his coat pocket, the man removed a small album of prints, along with a couple of ‘skins’ (an early form of condom manufactured from animal gut), which he jokingly invited the boy to try on for size. Hodson declined this invitation but began to peruse the album which, to his surprise, consisted almost entirely of printed erotica and images of a highly pornographic nature. The older man then asked the teenager if he would care to join him for a drink and a bite to eat at a nearby coffee house. On arriving at the establishment the lad was given cider, biscuits and another album of mucky prints with which to amuse himself, while his companion sat holding his hand and fondling him intermittently. The encounter eventually ended with the old gentleman giving Hodson a crown and asking him to join him for a drink again that Sunday.

Sir Richard Birnie. Birnie was a notoriously conservative London magistrate who had masterminded police operations against London’s radicals in the post-war years, culminating in the arrest and execution of the men involved in the Cato Street Conspiracy in 1820. By 1825 Birnie’s attention had begun to focus on the city’s gay community and he was responsible for the raid on the Barley Mow Inn.

Thomas Hodson would later claim that he saw nothing untoward in the man’s actions and that he’d simply considered him to be a “good-natured old gentleman” who was free with his affections and his money. Indeed he was so taken with the old man’s nature that he even invited a fourteen year-old friend to accompany him to meet the stranger at the Barley Mow Inn in the Strand on Sunday. When the boys arrived they found himwaiting for them in a private room where events proceeded much as they had before, the apprentices being plied with drink and distracted by albums of pornographic prints, while the stranger caressed and fondled them. Suddenly, the meeting was brought to an abrupt halt by shouts in the passageway and a loud bang, as a group of magistrates and watchmen burst through the door. The occupants of the room were dragged outside, through the ranks of a sneering mob which had gathered to watch the arrests and slung into the back of secure wagon which immediately whisked them away to the cells beneath the magistrates’ court in Bow Street.

It was at this point which the case took an unexpected twist which elevated it to the ranks of the sensational and scandalous. For it transpired that the old man at the centre of this sordid affair was none other than George Grosset Muirhead Esquire, the brother-in-law of the Duke of Atholl, Vice-President of the Auxiliary Bible Society of St George’s in the Fields and leading member of the Society for the Suppression of Vice. It was this upstanding pillar of London’s conservative community who now found himself languishing in a magistrates cell on charges relating to the indecent assault of two young boys.

While the courts of Hanoverian England were notorious for the swift and often brutal manner with which they dispensed justice, the wealthy could typically expect to receive a degree of leniency which reflected their elevated social status. Muirhead’s case may have initially appeared to be no different in this respect, with the magistrates opting him to spare him the humiliation of a public trial by holding the hearing behind closed doors in the Malborough Street magistrates court. However when his lawyers presented a case for the defence which smacked of this airily aristocratic indifference, claiming that no crime had been committed because the boys had consented to Muirhead’s advances, they were angrily slapped down by the judge who retorted that

In crimes of this atrocious description, consent or non-consent did not alter the defence, and it was an offence against public morals, not only because it was conducted in a public coffee-room, but because it was attempting to destroy the morals of youthful members of society.

Robert Cruikshank dubbed Reverend Percy Jocelyn ‘The Arse-Bishop’ in this caricature published by S.W. Fores in 1822. Clogher’s predicament was far more serious than that of Muirhead’s, as he had actually been caught committing the capital offence of buggery. He jumped bail, fled London and disappeared forever. Rumours surfaced years later which suggested that he had lived out his days under an assumed identity in a remote corner of the Scottish highlands.

The parade of well-bred witnesses that trooped through the court to speak in Muirhead’s defence also cut little ice with the judge, particularly when compared with the damning evidence presented by the prosecution. The two young victims, the officers who had caught the accused red-handed, Muirhead’s servants, his doctor, and even the printseller S.W. Fores were all called to appear against him, although the latter was excused from attending in person on account of his age and instead opted to submit a written statement for the court’s consideration. Fores’ testimony is interesting in that his evident attempt to distance himself from any notion that he had tolerated his shop being used as a homosexual cruising ground, was undermined by a later admission that the accused had been picking up young men from beneath the printseller’s window for the last sixteen years. Nonetheless, Fores’ claimed that he had tried to shame Muirhead into quitting the front of his shop by running to the windows and holding up copies of caricatures depicting the Bishop of Clogher. Clogher had been embroiled in an even more sensational scandal three years earlier, when a party of magistrates had kicked open the door to the backroom of a London tavern and found the Bishop engaged in a frenetic love-making session with a solider. The print Fores’ claimed to have threatened Muirhead with was almost certainly a copy of Robert Cruikshank’s The arse bishop Josilin g a soldier-or-do as I say not as I do (1822).

The guilty verdict was handed down by the court in short-order. Muirhead was sentenced to eighteen months in jail and order to pay a fine of £500, equivalent to over £35,000 in today’s money. His appeal, lodged on the grounds that prison was likely to be fatal to the health of a 72 year old man, was summarily dismissed, although the judge promised that he would be treated humanely by his jailers. In the end it appeared as though prison did little to dent Muirhead’s vitality as, three years after the affairs described above, he was arrested again on a charge of soliciting young men in the town of Dover. This time Muirhead was sensible enough to read the writing on the wall and after posting the huge sum of £1,000 in bail, he boarded a packet-ship in Dover harbour and fled to France where we was to remain in self-imposed exile for the rest of his life.

Notes and further reading

A full account of the Muirhead affair can be found in the Times of 25th August 1825 and in the various newspaper extracts reproduced by Richard Norton on his site:

http://rictornorton.co.uk/eighteen/1825news.htm

For a far more detailed analysis of the cultural and social significance of printshop window displays see, J. Monteyne, From Still Life to the Screen, Print Culture Display and the Materiality of the Image in Eighteenth-Century London, (2013)

Pingback: Merkwaardig (week 3) | www.weyerman.nl

Has anyone ever studied the fact that John Bowles (1753-1819), famous for his rants/stands against bad morals in England at the turn of the 18th century and an active member of the Society for the Suppression of Vice, was Carrington Bowles’ (1724-1793) younger brother?? (And thus, obviously, the son of John Bowles [1702-1779].) One wonders how they got along at family gatherings?! And one wonders if John Jr’s vocal stands against vice included the above topic of prints and print shops and were what antagonized his father John Sr to the degree that he essentially cut John Jr out of his will???

Yes, I can certainly image that it would make for a few interesting conversations over the dinner table.

I’m not aware of anything which would confirm or deny your suggestion and it might be worth checking the article on the Bowles family that Tim Clayton wrote for the ODNB to see if he covers it.

It’s funny, but I have yet to see anyone closely link John Bowles (1753-1819) to his family. Lots of people comment about his father’s words about him in his will but none seem to link THAT John with the mature, “famous” John Bowles (including the relevant entries in ODNB). (I am sure they are one in the same because if you look at John Bowles’ [1753-1819] own will, you will see mention of his sisters and sisters’ children, known to be John Bowle’s [1702-1779] progeny and grand-progeny.) I would LOVE to know what it was about “young” son John that ticked off his father to the degree that it did!

Gatrell mentions it in City of Laughter but doesn’t speculate on whether there was a link between John Bowles Jnr’s activities with the Society for the Suppression of Vice and his brother’s printselling business.

I suppose that John’s influence with the Society may have actually worked to the family’s advantage – The Society for the Suppression of Vice was known to send groups of busybodies around printshops and bookstores, to root out materials they considered as rude or seditious and to report the proprietors to the authorities. In 1822 (long after John’s fall from grace) they even succeeded in having S.W. Fores son thrown in jail for nine months after accusing him of selling pornography. One wonders whether John was ever tempted to direct the attentions of the Society’s agents towards printsellers who were seen as a commercial threat to his brother’s business? It certainly seems like a possibility, given what we know about his propensity for putting his morals aside when it came to matters of financial gain…

“Oh John Bowles!!” …. poor John Bowles – he gives another twitch in his grave as we speculate about his ulterior motives!

There’s another thing I’d love to know about John Bowles (and the London family per se) – what they thought about American William Augustus Bowles who visited London late in the 1790’s and was something of a popular celebrity at the time, if only because he liked to dress as an “Indian chief”. How would John Jr. react to someone who had “gone native”??? (I myself believe that William Augustus was John Jr.’s and Carrington’s nephew, but can’t yet find THE definitive piece of evidence to prove this.) Were there satirical prints about William Augustus Bowles’ visit to England – I need to search around I guess! (Sorry to get off the subject of your blog post and thanks for responding to me!)

Good question – There’s a mezzotint after Hardy’s portrait of W.A. Bowles in the British Museum collection (BM 1870,1008.2464) but I don’t think he appears in any caricatures that were published around that time.

Pingback: “Mark him out he is known on the town”, George Humphrey’s mysterious note | The Printshop Window

Reblogged this on timalderman.